a guide to Git's core concepts

I've never used another VCS before I learn the Git. So I do not know much about other VCS's details. But maybe this is a good thing because you must not apply your past knowledge of another VCS to Git. Many people think that Git is hard to learn. Maybe this is one of reasons.

But complex systems like Git become much easier to understand once you figure out how they really work. Here something that could at least explain some details of how Git works under the hood will be talked about. We are going to take a look at some of Git's core concepts including its basic object storage, how commits work, how branches and tags work. So we won’t tell you how one command in Git is used. We want to tell you something behind Git's commands. Hopefully, at the end of it all, you'll have a solid understanding of these concepts and will be able to use some of Git's more advanced features with confidence. So remember that this guide is NOT intended to be a beginner's introduction to Git.

Repositories

At the core of Git is the repository. A Git repository is really just a simple key-value data store. This is what is stored in Git:

- Blobs, which are the most basic data type in Git. Essentially, a blob is just a bunch of bytes; usually a binary representation of a file.

- Tree objects, which are a bit like directories. Tree objects can contain pointers to blobs and other tree objects.

- Commit objects, which point to a single tree object, and contain some metadata including the commit author and any parent commits.

- Tag objects, which point to a single commit object, and cotain some metadata.

- References, which are pointers to a single object(usually a commit object or a tag object).

The import thing to remember about a Git repository is that it exists entirely in a single .git directory in your project root. The import directories are .git/objects, wherse Git stores all of its objects, and .git/refs, where Git stores all of its references.

Tree Objects

A tree object in Git can be thought of as a directory. It contains a list of blobs(files) and other tree objects(sub-directories).

Given the root tree object, we can recurse through every tree object to figure out the state of the entire working tree. The root tree object, therefore, is essentially a SNAPSHOT of your repository at a given time point. Please be careful to notice the concept SNAPSHOT, because it is one main reason of Git's high fficiency.

Commits

A commit object is essentially a pointer that contains a few piece of important metadata. The commit itself has a hash, which is built from a combination of the metadata that it contains:

- The hash of the tree (the root tree object) at the time of the commit. As we learned in Tree Objects, this means that with a single commit, Git can build the entire working tree by recursing into the tree.

- The hash of any parent commits. This is what gives a repository its history: every commit has a parent commit, all the way back to the very first commit.

- The author's name and email address, and the time that the changes were authored.

- The committer's name and email address, and the time that the commit was made.

- The commit message.

git show --format=raw COMMIT-ID

Using this command, we can see the newly-created commit's metadata.

Reference

First of all, we need to know that every object in Git is indentified by a hash. But you must remember the hash of every object you want to manipulate. To save you from having to memorize these hashes, Git has references or "refs". A reference is simply a file stored somewhere in .git/refs, containing the hash of a commit object. Git can tell us which commit a reference is pointing to with the show and rev-parse commands.

$ git show rev-parse master

e439c576b191fd9cb797fd9a27f4b7c617abfd21

Git also has a special reference, HEAD. This is a "symbolic" reference which points to the tip of the current branch rather than an actual commit. It is actually possible for HEAD to point directly to a commit object. When this happens, Git will tell you that you are in a "detached HEAD state".

Branches

Branches in Git are very lightweight which is why Git's branches are generally thought as its strongest features. The reason branches are so lightweight in Git is because they're just references. Two types of branches are local branches and remote-tracking branches.

Tags

There are two types of tags in Git - lightweight tags and annotated tags.

On the surface, these two types of tags are very similar. Both of them are references stored in .git/refs/tags. However, that's about as far as the similarities go. Real differences are between lightweight tags and annotated tags.

By default, the command git tag will create a lightweight tag. But pay close attention to this tag which is not a tag object. It is just a reference which points to the current commit object.

Now let's see the annotated tags:

$ git tag -a -m "Tagged 1.0" 1.0

This command will create an annotated tag named 1.0. Here what needs much more attention is that it create a tag object, not a tag reference. A tag object is separate to the commit that it points to. As well as containing a pointer to a commit, tag objects also store a tag message and infomation about the tagger. Tag objects can also be signed with a GPG key to prevent commit or email spoofing.

Merging

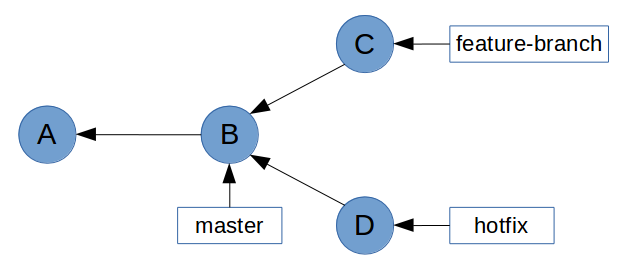

Merging in Git is the process of joining two histories(usually branches) together. Say we have created two branches from master and done some work respectively. At this point, the history will look something like this.

Now we can bring the bug fix into master so we can tag it and release it. Let's see what happens after merging.

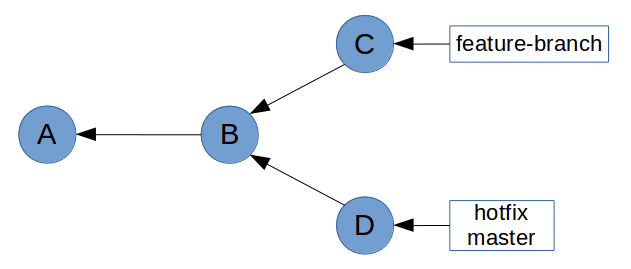

We can see how Git mensions fast-forward during the merge. What this means is that all of the commits in hotfix were directly upstream from master. This allows Git to simply move the master pointer up the tree to hotfix.

Then let's try and merge feature-branch into master.

This time, Git wasn't able to perform a fast-forward. This is because feature-branch is not directly upstream from master. When coming to this situation, Git actually creates a new "merge" commit whose parents are from feature-branch and master. And this is referred to as a merge commit.

Next we'll see how to prevent this kind of non-fast-forward merges by rebasing feature branches before merging them with master.

Rebasing

This part is gonna be hard because of the extrordinay amount of scaremongering around rebasing which you can read from the Internet. First of all, let's take a quick look at the cherry-picking. I'm gonna tell you that cherry-picking exists in a special situation from rebasing.

Cherry-picking

What git cherry-pick does is take one or more commits, and replay them on top of the current commit. It's like you get a patch from one commit and apply it on your current commit. All git cherry-pick does is apply one from a commit one by one. But what if you want to play a chain of commits on the other one, e.g., master branch. Actually, you don't have to use git cherry-pick command many times.

rebaseing (continued)

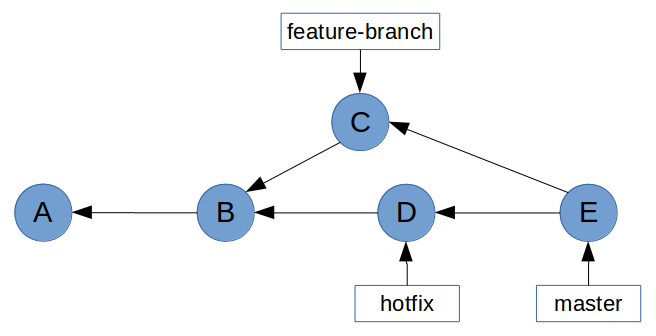

$ git rebase master foo

With the format git rebase <base> <target>, the rebase command will take all of the commits from <target>, and paly them on top of <base> one by one. It does this without actuall modifying <base>, so the end result is a linear history in which <base> can be fast-forward to <target>.

For now, I'm done. But there will be more contents.